This article originally appeared on Rewire.org on February 10th. All episodes of Spy in the Wild are now streaming here.

By Katie Moritz

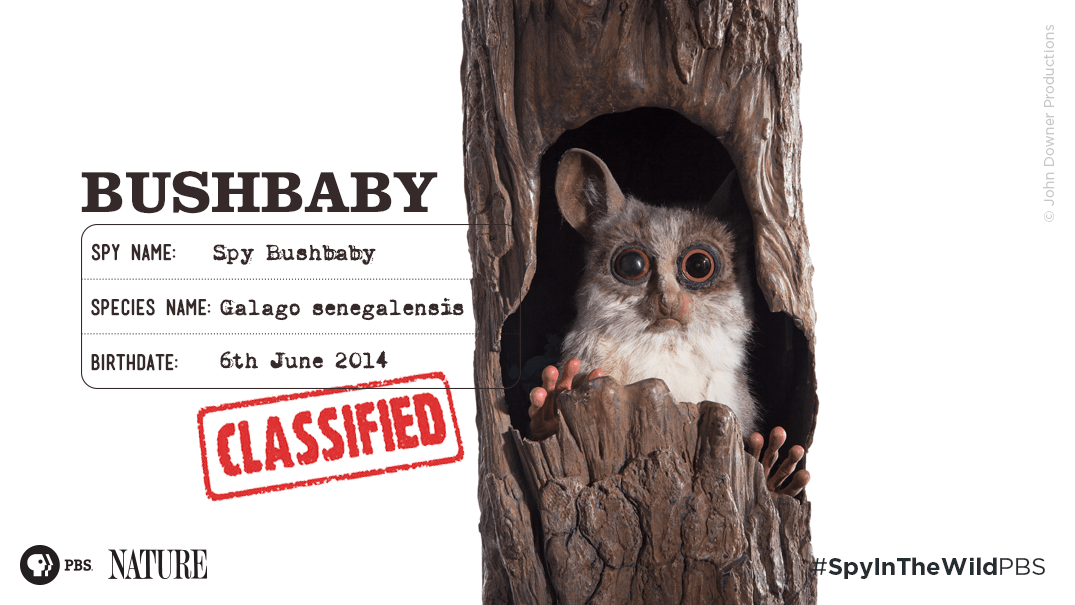

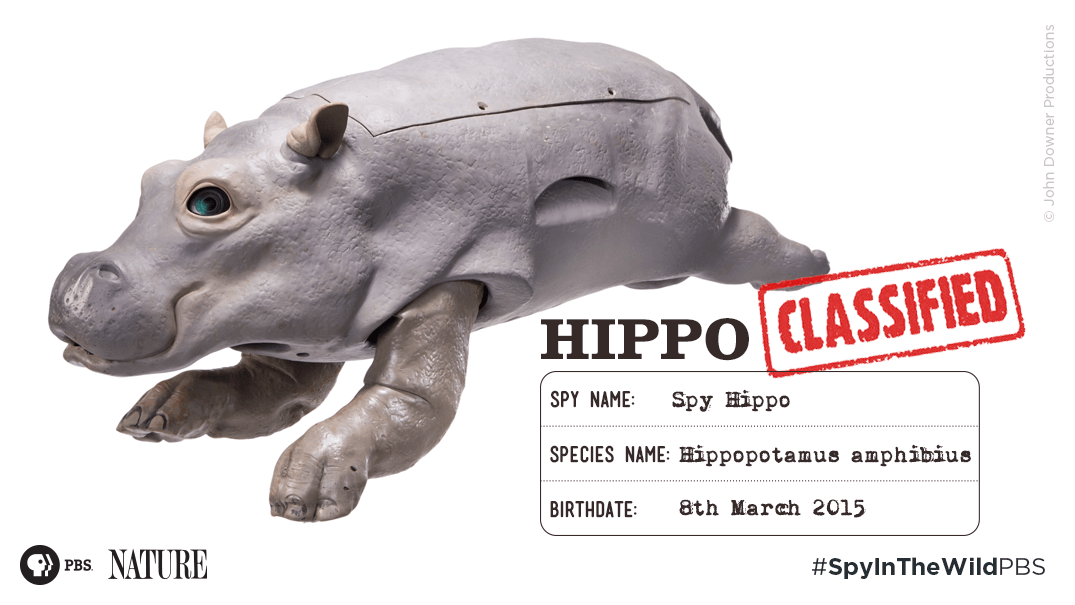

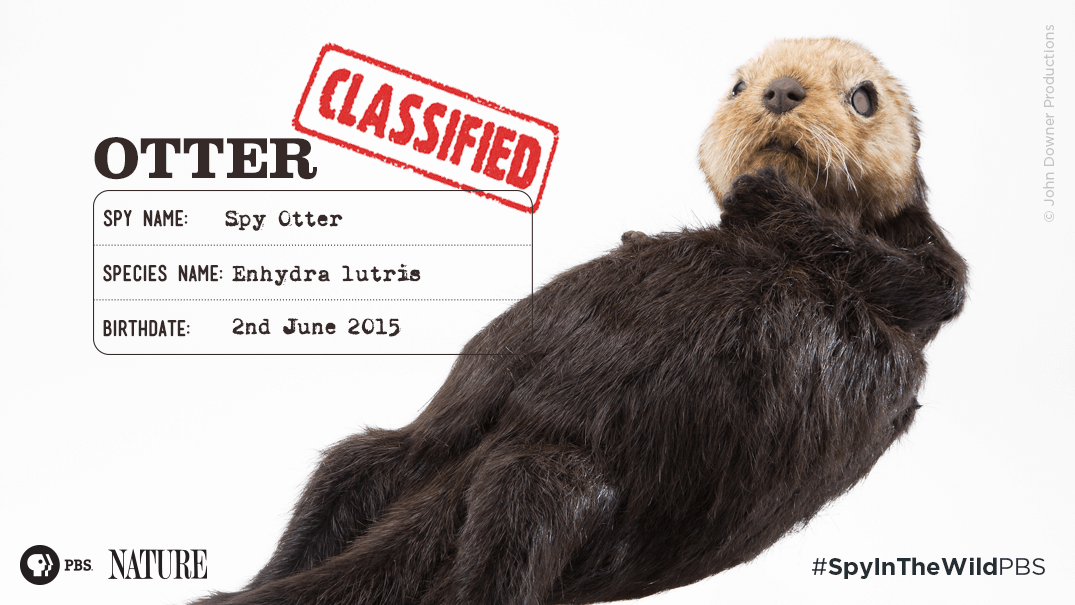

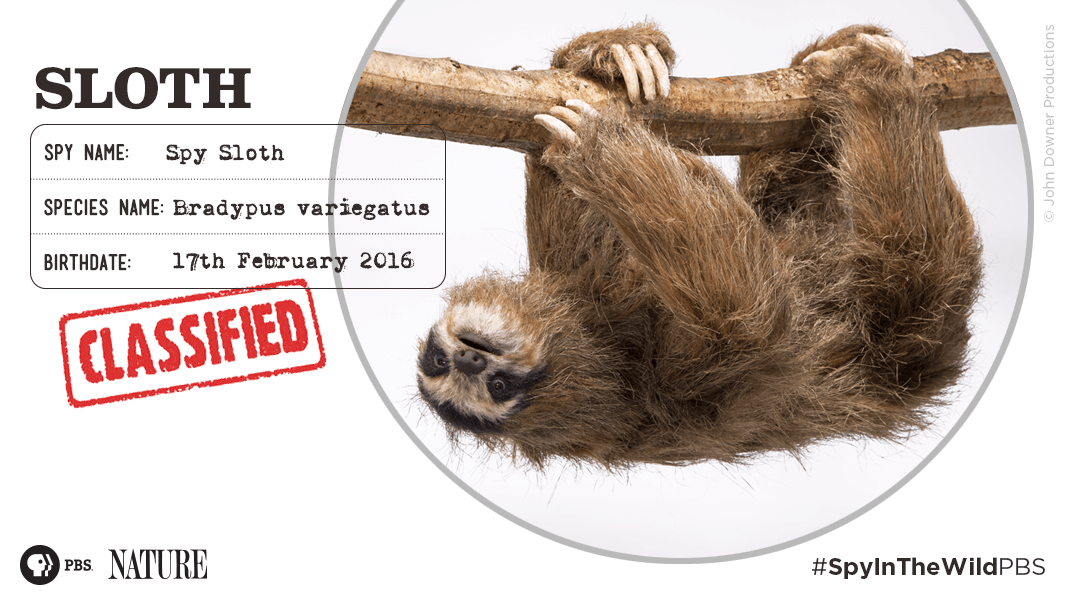

They’re cute. They’re cuddly. They’re robots and cost thousands of dollars and hundreds of hours to make. I’m talking about the furry and scaly army of more than 30 “spy creatures”—life-like robot animals equipped with hidden cameras embedded in their eyes—created for the PBS and BBC program “Spy in the Wild” to infiltrate herds of real animals and give us a never-before-seen look at how they interact.

“Spy in the Wild” is now airing in the U.S. on PBS as a miniseries of “NATURE.” Series producer Rob Pilley of John Downer Productions in the U.K. helped create the program—and the creatures—over more than three years. The series was filmed on every continent in more than 21 countries and territories. Pilley talked with us about what it takes to film animals in the wild what’s next for the spy creatures.

Rewire: Planting robot creatures among real ones is kind of an out-there idea. Where did it come from?

Rob Pilley: The concept of the spy series was 16 years ago (with the) boulder cam. It was a camera disguised as a lump of rock for “Lions: Spy in the Den.” Then there was “Elephants: Spy in the Herd” and “Bears: Spy in the Woods.” Each one of them is never the same, always featuring an evolution of the spy cameras becoming more and more complicated with time. The animals could carry (the hidden cameras) around, bash them around.

The first of the spy creatures was born for “Penguins: Spy in the Huddle.” We were actually taking part in behavior, which was the first that anyone’s ever done anything like that.

Then it sort of led us to do another spy series which was called “Dolphins: Spy in the Pod.” We had 13 different spy creatures for that one. That was really an evolution in terms of development of numbers and diversity.

(Then we thought) rather than focusing on one particular animal, why don’t we have a whole array of different spy creatures all around the world in all the different habitats? We now have 34 different spy creatures, all of them do a very different job, in different landscapes around the world having very different experiences with the animals.

Rewire: How long did it take to develop the creatures?

RP: The first-ever spy creature was the meerkat and that took three or four months. It was a prototype robot that could move and look around, it had a camera in its eye. They on average take three to four months, maybe six months. The walking crocodile took nine months to a year.

When you have a relatively static spy creature like a meerkat or a wild dog, it can look around, move its head around, but when you get to the actual walking devices… suddenly you’ve gone beyond the realms of animatronics and into the realm of robotics. Not only have they got to look the part—they have to look absolutely lifelike—they have to walk the part, and with robotics inside of the walking ones, they need robotic specialists. So, you cant just go to an engineer and say, hey, can you build me a spy egret or a spy peccary.

We have to turn to one of our roboticists who are either based in Japan or Switzerland. From there it we need to bring it back to the U.K. where our animatronics guys will build up layers of skin and feather or fur to make the thing come alive and look the part. It’s a whole creative process that these things have to go through. It takes a very long time and often the robot has to go backwards and forwards between the guy who’s building the skin for it or the feathers and the guy who’s built it originally. It can be a very taxing, very tedious task sometimes.

Everything we make is totally bespoke, even the cameras that are in the eyes are bespoke. You can’t just buy them off the shelf. So you’re having to bring these multidisciplines in, often very academic disciplines when it comes to robotics. These are guys that are very good at working in the lab but when it comes to taking them out in the field in the dust and humidity they’re very much out of their comfort zone. And it plays havoc with the devices—heat has been a big problem for us. Cameras get very hot in the best of times. Putting them out in the blazing sunshine, it only goes to make them overheat more quickly. It all adds to the complication of it all.

Rewire: How did you decide which animals to create?

RP: For any one program, what we did was look into essentially the most emotional animal species that are out there—those who exhibit the most human-like behaviors, those who openly have physical contact with each other, very good bonding relationships with each other.

As far as producers and directors, we’re all biologists, I’m a zoologist—we’re beyond filmmakers, we’re very much animal people first and foremost. We then take the advice of over 20 scientific advisors we’ve used on this series on what they think is possible. When everyone agrees, this is very doable, this is very possible (that’s when we talk about building a spy creature). For example, with the elephants, the obvious choice would have been to build a baby elephant. That would have been very cute but it would have been very complicated. Elephants are highly sensitive animals and they’re incredibly smart. There’s no way you cold have fooled an elephant (with a robotic baby elephant). The cattle egret hangs along with elephants an awful lot (so we made one of those). He’s still alive to this day thank goodness.

Rewire: When you’re filming in the wild, how do you know to be in the right place at the right time to capture the perfect moment?

RP: Before we actually go out and film a story we do a lot of research ourselves. We look at where (animals are) going to gather in good numbers or are relatively habituated. For example with the crocodile sequence (in the first episode), where you see the mother crocodile picking up the babies, that was shot on the River Nile in Uganda. The reason I chose to go there is because (that location) has one of the highest densities of crocodiles in the world also because it’s a national park. There are a lot of tourists who go along on riverboat tours (so) he crocodiles are relatively habituated to people.

One of the biggest problems with crocodiles is they’re incredibly sensitive, they’re so incredibly sensitive to sights and sounds. Getting close to wild crocs is actually hard, particularly wild crocodiles when they’re on their nest. They’re very sensitive to anything coming near them, they’re all very vulnerable when they’re up at the bank. (Our advisors told me) the behavior of the mother tending to her nest had never been filmed in the wild, because those animals are so nervous it’s unlikely are you going to get near them, and in no way will you get this behavior. I said, I’m suggesting we can deploy remote cameras, which we can deploy when no one else is around.

We were there for three weeks. We’d deploy the cameras and retire to a safe distance and we’d wait. We discovered as well that when a mother crocodile is tending her a nest she picks them up in her mouth and turns them and turns them very gently to encourage them to hatch out, which is fine when you’re an egg that’s got a baby inside, because you’re relatively fleshy and soft, you can tolerate a bit of a pummeling. But when you’re a hard piece of carbon fiber and aluminum… you do get smashed to pieces, and as a result we lost six of the spy crocodiles that way in their very overzealous mum’s mouth. We had to go back three times, but we finally managed to put together the pieces for the sequence.

You have to get under their skin, you have to work out their daily routine. We use our biological backgrounds and understanding of behavior to go out and observe, right, that’s the common denominator, they regularly go to this spot, it’s an area they’re habituated to. Not only are you potentially introducing what they think is a new animal amongst them, you’re also releasing your most valuable, your most fragile, your most expensive piece of kit. The last thing you want to do is deploy that and have it destroyed on the first day. I’ve been out there for two weeks without ever deploying a spy creature. When you’re 100 percent ready, that’s when you deploy. You always treat every deployment as it’s your last. You literally say goodbye to them, because you think you’re never going to see them again.

Rewire: Did any of the robotic animals get rejected by the real ones?

RP: No, as far as the elephants with the egret, they would go right near it, and no one would bat an eyelid. One thing they weren’t overly keen on was the spy tortoise. They’ve got very sensitive smell, and so as much as he looked the part they could smell that he wasn’t quite right, even though we covered him in mud and dust and elephant droppings as well.

They did accept him in the end to the point where they picked him up, which was great. But he does get completely flattened, they squash him. That wasn’t aggression, they were intrigued by what it was. They actually have very sensitive feet, they can feel vibration through the bases of their feet. They can feel an awful lot with those feet. When they come across something they’re not sure about, they feel it with their foot, they actually scan the things with their feet. If they’re still not satisfied, they actually place their foot on it they press on it. The tortoise, they leant on it and completely pancaked it.

Rewire: What’s your favorite moment that made it into the series?

RP: The crocodile sequence when we finally went into the mouth was quite a monumental moment. To find out that it never, ever had been observed in the wild was groundbreaking to me. The fact that everything was stacked against us, it was totally unlikely we were going to get it, but because we knew the way the devices worked and trying to be pioneering, which is what we always try to do, it was a very proud moment when we finally got in there to see how gentle she is with those babies. It’s a bit like going to space, inside a predator’s mouth like that—you don’t generally do that everyday.

Rewire: What’s next for you and the spy creatures?

RP: We’re straight into the next series, which is promising to be faster, higher, quicker, better. So in a few years’ time there will be a follow-up series that will see the spy creatures being even more complicated, even more involved, flying higher, running faster, digging deeper and getting closer to animals than ever before.

Take a look at some of the spy creatures created for the program:

![]() This article originally appeared on Rewire

This article originally appeared on Rewire

© Twin Cities Public Television - 2017. All rights reserved.

Read Next